‘Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose’

Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr, French critic and novelist

Having spent a fair part of yesterday drafting our call for Suella Braverman to go — she's gone!

Monday mornings don't often start with such dramatic changes, but the new top team in the UK Government offers real promise: not just for stability in the United Kingdom, but also globally.

David Cameron is an excellent choice as the new Foreign Secretary: not just by virtue of his experience but also due to his constructive approach towards international convergence. We're not harping back to Brexit in saying that: long-term readers of this commentary will recall our views on EU dysfunctionality.

The urgency now is for global convergence and for strengthening the democratic legitimacy and authority of the United Nations, as we called for on 14th November last year. It's about long-term governance in a world beset by global challenges of conflict, climate change and inequality.

David Cameron will do this job well, and in due course even the right wing of the Conservative Party will come to appreciate that — together with the positive influence he is likely to have for next year's election. Meanwhile, James Cleverly is a good choice for Home Secretary, and will help re-balance the Government’s relationship with the police after last week’s debacle.

Who should stay, who should go?

The news this morning has all been political, but challenge to leadership is not just in that arena.

It's at times like these that the Christian faith has so much to offer, as we explained on 30th October, in calling for servant leadership. At our local remembrance service on Sunday, the Assistant Archdeacon of Buckingham spoke eloquently on the need to add an additional freedom to Franklin D. Roosevelt 's list of four (speech, worship, want and fear), which he set out in his 1941 speech. The Assistant Archdeacon has kindly provided a text of his talk, which is well worth a read.

The Christian Church is not, however, without its own hot issues of community integration, although fortunately not with anywhere near the same devastating consequences as we are witnessing in the Middle East. This week the General Synod of the Church of England will be considering for the umpteenth time its decisions on ‘Living in Love and Faith’ — its euphemism for how to approach same-sex relationships. Attitudes have hardened between the two opposing factions and last Friday they burst into the ‘Thunderer’ column in The Times, with General Synod member Jayne Ozanne calling for Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, to stand down over the issue.

So, once again — who should stay, and who should go?

Having been a General Synod member myself from 1995 to 2021, I'm well aware of the extent to which this issue has consumed the attention of the Church. When it should be dealing with the really big issues, the most important of which at present is what is meant by Jesus’s instruction to ‘love your enemy’, the Synod will be wasting two days of its time wrangling over an aspect of human behaviour where Jesus showed clearly why it’s a second level priority. Our podcast ‘Love at the Cutting Edge’ demonstrates this clearly, including the need to use our conscience as opposed to applying our judgement.

Archbishop Justin's approach is, in fact, very focused on integration, by encouraging people to be reconciled with each other’s differences. This was quite a contrast to his predecessor Rowan Williams, who really struggled at trying to get everyone to agree. Justin just asks people to show respect and love to each other and to get on with life as it is: a recipe which should lead towards, not away from, peaceful co-existence, because it is essentially about loving our neighbour who is least likely to be our neighbour (again, as Jesus taught). So Justin should stay.

Next year we’ll be surrounded again by questions of who should stay and who should go, with elections coming up in both the United Kingdom and the United States. The airwaves will be thick with the voices of those who think they know best, and who want to impose their own ‘solutions’ on people who are generally well-equipped to sort things out for themselves, without the frequently chaotic and invariably heavy-handed oversight of governments throwing their weight around.

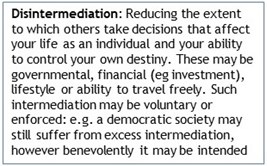

On both left and right, politics brim with people who think they know best: meanwhile in the centre-ground the desire to control is no less evident. There is a major gap in the political spectrum for those who believe that disintermediated individual participation for all is a worthwhile objective combined, of course, with a reliable safety net for those who are not able to make their own way.

On both left and right, politics brim with people who think they know best: meanwhile in the centre-ground the desire to control is no less evident. There is a major gap in the political spectrum for those who believe that disintermediated individual participation for all is a worthwhile objective combined, of course, with a reliable safety net for those who are not able to make their own way.

On Wednesday 22nd November UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt will deliver his Autumn Statement, an important indicator of the UK Government's priorities as it enters the election year. We've been crystal-clear on the economic issues that matter, in our view: the injustice of freezing tax thresholds at a time of high inflation, the need for wealthy older folk to pay for their own NHS healthcare through mandated private health insurance, and the need to hypothecate a good proportion of inheritance tax receipts to enable inter-generational rebalancing — and to reform the structure on which the inheritance levy is charged.

Of course, Jeremy Hunt needs to keep the lid on inflation, and it's now relatively certain that at least one of Rishi Sunak's five pledges will be met in this regard. So if, as predicted in The Times last week, he decides that that it's time to follow in Nick Clegg's footsteps in leaving politics in order to take a senior role in giant tech, will Jeremy Hunt step forward for leadership with more success than before? Time will tell: as listeners to this commentary will be aware, we're not strong supporters of financiers taking the reins. Perhaps we might yet see David Cameron taking the hot seat in repeating his post-coalition experience of losing a partner to giant tech?

In an ideal world the question of who should stay and who should go should gradually reduce in significance, as people across the world participate in individual ownership and responsibility of the things that matter to them, and as they learn to build respect for others, no matter how different they may appear.